The world is increasingly globalized these days, and businesses are no different. With a presence in multiple countries, global businesses face exchange rate risks.

If you find yourself wondering about how global companies handle currency fluctuations, then you’ve come to the right place.

In this guide, we’re going to show you three brilliant methods that companies use all the time.

Are you ready?

Great! But first, let’s look at what currency fluctuation means.

Currency Fluctuations (AKA Exchange Rate Risk)

Every multinational company is exposed to exchange rates. In simple terms, currency fluctuation means that a firm’s profitability might change because of a change in exchange rates. This is often called exchange rate risk.

Let’s illustrate this through a simple example.

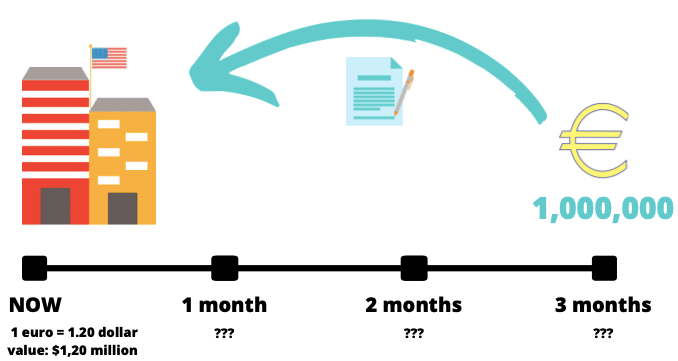

Say that you are a US firm and that the current EUR/USD rate is 1.20 (One euro is worth 1.20 dollars). You just won a contract for delivering goods worth €1,000,000 and payment is due within three months. You’re very happy with the order and book a revenue of $1.20 million at the current exchange rate.

The problem arises from the fact that the delivery of goods and the subsequent payment don’t happen immediately.

By the time you are paid three months later the EUR/USD rate will most likely have changed. This can have disastrous effects. For instance, if the rate decreased to 1.10, you would only get $1.10 million, $100,000 less than you had anticipated.

Of course, a rate change can also be favorable. If the rate increased to 1.30, your sale would worth $1.30 million instead of the expected 1.20 million, which would be quite a nice surprise, wouldn’t it?

That said, for those with a mind for business, the risks of an unfavorable change in exchange rates far outweigh the potential for gain. It is for this reason that global businesses design methods to minimize the effects of currency fluctuations.

How Do Global Companies Handle Currency Fluctuations?

When global businesses design methods to handle currency fluctuations, the usual goal is to minimize the change in expected cash flows arising from fluctuating exchange rates.

As illustrated above, while this change is not always bad, the possibility of being negatively impacted is usually enough of a concern for most firms to take action to reduce exchange rate risk.

The term used to describe this procedure is hedging.

The origin of the phrase comes from the idea of using hedges or plantings to act as a fence to enclose a piece of land; a hedge delimits an area, in the same way that hedging limits risk.

While hedging can be often complex in practice, the idea is fairly simple. The company takes a market position that moves in the opposite direction than the currency causing the risk. The position will then offset any fall or rise in the value of the currency.

Consider this simple analogy to make the concept more digestible:

If you are afraid of increasing gas prices, you might buy shares that benefit from the inflation of oil prices. The price of these shares will most likely rise with the price of oil and offset some portion of your gas bills. If gas prices tumble and your shares go with them, your losses will be mitigated because you will pay less at the gas station.

Hedging in a multinational environment follows a similar logic, but typically involves more complicated financial products. There are also added challenges, such as finding the right combination of these financial products to best neutralize the risk of different cash flows.

In the following sections, we’re going to take a look at three different ways global companies can hedge exchange rate risks.

Money Market Hedge

The money market hedge is fairly simple to understand. The company borrows in one currency and exchanges the proceeds for another currency. The loan is repaid with funds generated from business operations.

Let’s see an example.

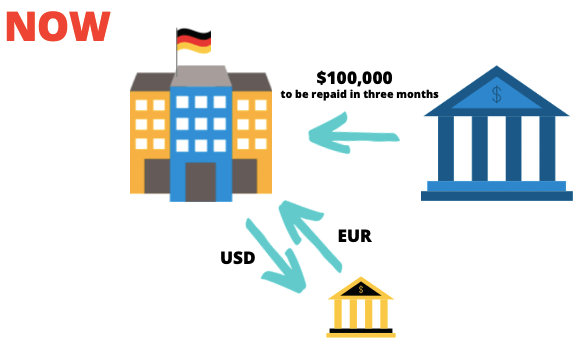

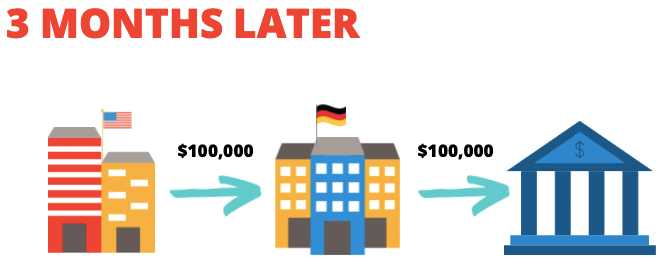

Imagine that a German company has a sale worth $100,000 to an American customer. The customer will pay in three months’ time. The German company thus faces the risk that during the following three months the dollar might depreciate relative to the euro.

The appropriate money market hedge technique here would be to borrow US dollars in an amount matching the size and maturity of the expected dollar payment. That is, the German company would borrow $100,000 and would promise to repay in three months. The borrowed dollars would then immediately be converted into euros at the current market price.

This way the German company immediately gets paid in its home currency and avoids risking that over time the dollar might lose its value relative to the euro. When the American company posts the $100,000 payment three months later, this will then be used to repay the USD loan.

Of course, this is a simplified example, because we have ignored that loans have interest rates.

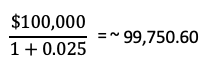

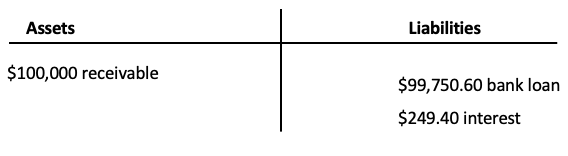

So, in practice, the German company will need to borrow less than $100,000, so that the receivable from the customer is enough to repay both the loan and the interest. For example, if the borrowing interest rate is 2.5% for three months, then the amount to borrow now for repayment in three months is

Thus, the German company will only borrow ~$99,750.60 and, in three months, repay that amount plus $249.40 of interest with the account receivable. In effect, the interest is the cost of the hedge, which the company pays to eliminate the exchange rate risk.

To summarize, the money market hedge works by matching assets and liabilities according to their currency of denomination.

Forward Market Hedge

The forward market hedge is slightly more complicated to understand if you don’t have a background in finance. But don’t worry, we’ll explain.

A forward contract is an agreement to buy or sell an asset at a certain time in the future for a certain price. In layman’s terms, it allows companies to lock in a reasonable price to be paid at a future date and thereby eliminate any potential gains or losses from exchange rate changes.

This “reasonable price” is called the forward price. Banks and other market makers establish forward prices for several time horizons using interest rates.

These forward quotes are readily available to clients, much in the same way as immediate (spot) prices are available. For example, a bank might indicate that it is prepared to buy GPB immediately at the rate of $1.4542. It might also indicate that it will buy GBP at $1.4544 in 1 month, at $1.4547 in 3 months, and at $1.4556 in 6 months.

| Spot | 1.4542 |

| 1-month forward | 1.4544 |

| 3-month forward | 1.4547 |

| 6-month forward | 1.4556 |

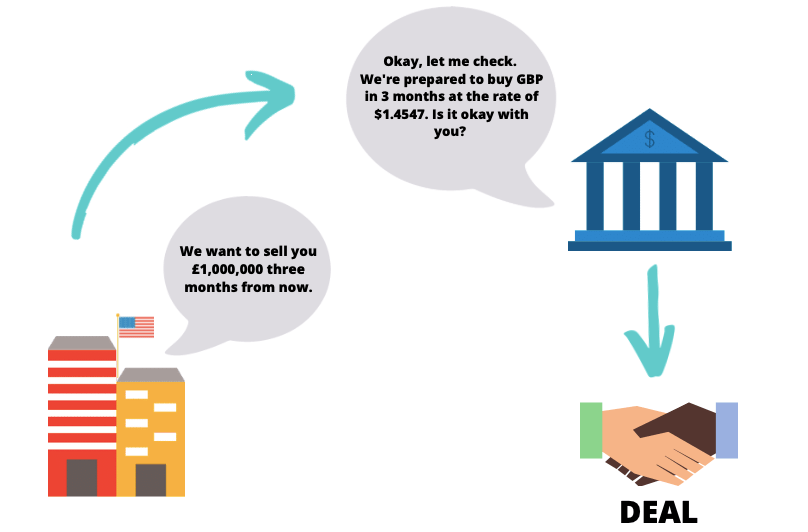

Suppose that an American company has a foreign currency denominated sale worth £1,000,000. Using the current spot rate offered by the bank, it books the receivable as $1,454,000. Further assume that the current month is January, and the company will receive the GBP payment three months later in April.

A forward hedge involves entering into a forward contract at the time the currency risk is created.

Should the American company wish to hedge its transaction exposure with a forward hedge, it will go to a bank in January and agree to sell it £1,000,000 three months later in April at the 3-month forward rate of $1.4547. This agreement eliminates the exchange rate risk.

In three months, the American firm will receive £1,000,000 from the buyer, deliver that sum to the bank to fulfill its obligation, and receive $1,454,700 in exchange regardless of the market price.

Notice that this amount is $700 more than what the American company recorded at the time of the sale. Thus, the American company must record on its income statement a foreign exchange gain of $700.

Since this gain is known immediately after the forward contract is agreed on, you might be tempted to think that this forward was a particularly good deal. This is misleading, because forward rates reflect market expectations and the price of risk; thus, they can just as easily cause a foreign exchange gain as a foreign exchange loss on the income statement.

The eventual payoff from the contract to the company depends on the difference between the forward rate and the current market rate on the date when the contract expires.

For instance, if the market rate 3-months later turns out to be $1.50, then the forward contract will have a negative value to the company because it is contracted to sell £1,000,000 for $1.4547 resulting in $1,454,700, which is below the current market value of $1,500,000.

Options Market Hedge

When it comes to how companies handle currency fluctuations, a third possible answer is that they use options.

To understand how an option hedge works, we must first clarify what options are, and explain some basic terminology.

An option contract offers the buyer the opportunity to buy or sell something.

In particular, there’re two types of options. A call option gives the holder the right to buy an asset by a certain date for a certain price. A put option gives the holder the right to sell an asset by a certain date for a certain price.

The price in the contract is known as the exercise price or strike price.

Consider the following situation:

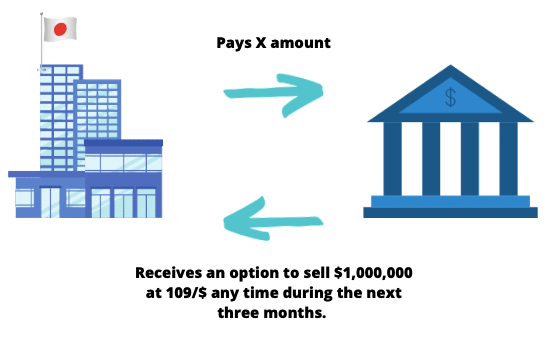

A Japanese company has a dollar denominated receivable due in three months. The amount of the receivable is $1,000,000 and the current exchange rate is ¥110/$. If the receivable was paid today, the Japanese company would book a ¥110,000,000 revenue in cash. Since the receivable is settled three months later, there’s the risk that this amount might decrease.

To hedge against this risk, the Japanese company could purchase from its bank a 3-month put option on $1,000,000 with the strike price of ¥109/$.

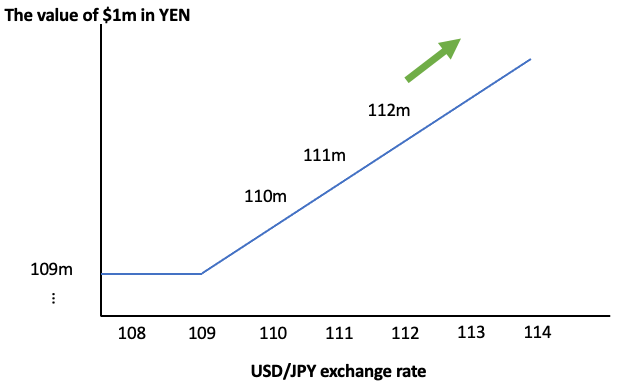

When the $1,000,000 is paid in three months’ time, the value in Yen depends on the spot rate at that time.

For instance, if the Yen depreciates to ¥114/$, the company will simply leave its option unexercised and exchange the $1,000,000 for ¥114,000,000. This is well above the ¥110,000,000 that was originally budgeted and the ¥109,000,000 stipulated by the option.

Leaving an option unexercised is possible because, as the name implies, an option gives the holder the right, but not the obligation to do something.

This feature of options allows companies to benefit from a favorable outcome in the price of the underlying currency while, limiting downside risk to a known amount.

In our example, the upside potential for the Japanese company is unlimited because there’s no limit to the weakness of the yen (or to the strength of the dollar for that matter). At any exchange rate above ¥109/$, the company would allow its option to expire unexercised and would exchange the dollars for yen at the spot rate.

Now consider what happens if the yen strengthens against the dollar. If the exchange rate depreciates below ¥109/$, the company would exercise its put option and sell $1,000,000 for ¥109,000,000.

The downside risk with options is usually worse than with a forward or money market hedge. However, unlike these alternatives, the option hedge leaves room for huge upside potential.

Conclusion

When global companies take measures to protect themselves from currency movements, this is referred to as hedging. In this post, we’ve seen how the money market, forward contracts, and options can be used to hedge exchange rate risks.

Forward contracts are designed to neutralize risk by fixing the price that companies will pay or receive for the underlying asset. Option contracts, by contrast, work more like insurance; they offer protection from adverse price movements, without removing the chance to benefit from favorable price movements.

A money market hedge is typically more difficult to organize than a forward or options hedge, but it can provide yet another alternative to companies seeking to minimize the impact of currency movements.

Despite best efforts, currency movements are still a significant source of headache to companies. For example, there can be uncertainty as to the exact date when a foreign currency will be bought or sold and thus it is more difficult to manage the risk.

So in practice, hedging is often not quite as straightforward as this guide would let you think. That said, we hope you found this article informative and are now familiar with some of the ways in which global companies handle currency fluctuations.